NOSTALGIA INTERRUPTED

Preamble by Ingrid Jones

Nostalgia makes a lie go down a little bit easier.

—Dr. Herman Gray

My nostalgia is fraught. A fusion of West Indian and North American, Lover’s Rock and Radiohead and ackee and saltfish and butter tarts. It is the moment in high school that I naively suggested to a white friend that they pick up the latest issue of Essence when they spotted the cover amongst my newly purchased haul of magazines. When I explained that the publication was like Vogue, except for Black stories, fashion and music, my friend stared at me quizzically and replied, “Why would I want to read that?” It never occurred to me that my world would not be of interest after a lifetime of consuming media dedicated to hers.

It is the realization in adulthood that during those dreamy years of childhood in the 70s, my parents were subject to all manner of painful indignities. They bore the brunt of stares and whispers as one of a handful of Black families in small-town St. Thomas, Ontario, where I was born. A city in which the local priest refused to baptize me and, Sunday after Sunday, my parents watched as he called every white family to the altar but not them. After that, my father stopped attending church for over two decades.

My nostalgia is my parents’ silver Volvo. Like any other teen, I borrowed their car – only after going over “the rules.” I was stopped nearly every time I drove. In particular, was the night I was on the way home from a club only to be surrounded by six squad cars and twelve officers at three am for a burned-out tail light. With guns drawn and flashlights blinding my eyes, I was threatened with the impounding of my vehicle even though I lived just blocks away. I was terrified and alone on a dark stretch of road next to a highway. When I called the precinct to file a complaint about the aggressive nature of the interaction, the sergeant told me perhaps, the officer who initiated the stop “was having a bad day.” Now I only remember the fear, not the joy I probably felt amongst friends on a crowded dance floor.

My nostalgia is fraught.

In the past few years, nostalgia has made a comeback. Not just in the form of flared denim, Barbiecore or oversized shades, but in our political climate, media and legislation. Unlike the expected romanticism, this resurgence is of insidious proportions. It whispers sweet nothings to a white base fearful of globalization with slogans such as “We want our country back” and “Make America Great Again.” It touts The Great Replacement1,2,3 and asks its followers to “…stand up for the values that make this country great”4 while threatening to screen potential Black and brown immigrants for “Canadian values.” This sentimentality, that waxes poetic about whites having “the strongest bloodlines”2 while bequeathing eerily familiar images of white men with torches marching through the American south5,6,7,8 alongside stoic musings of the ‘good ole days’, is not inclusive. It is a stark reminder of the complexities involved in BIPOC nostalgia, one consistently interrupted by terror, inequality, disposability, fear and aggression.

In this age of easy access to the historical realities of BIPOC, it could be assumed that any effort to use nostalgia to gain power and influence, would fall flat. But in fact, the contrary has happened. We are living in an age of rampant disinformation. One in which there has been little to no desire amongst a dominant class to share that dominance beyond a performative social media square and even less acknowledgement that media depicting BIPOC lives continues to dehumanize us to an alarming degree.

In contrast to the glut of imagery glamourizing the stories of white culture and society, there was, and still is, little to no example of what our reality is and what nostalgia means for us.9 To say that ‘Times were better then,’ glosses over the grave hardships our communities faced and continue to face – the many times our lives are consistently and, at times, brutally whiplashed into states of fight or flight. It ignores our aspirations and the various forms of resistance we continue to employ in the face of persistent systemic discrimination.

This sentimentality is not inclusive.

The recall of a greater past often stems from the implicitly biased memories of a predominantly white and male-dominant class born in the silent and baby boom generations. Their powerful grip on all forms of media production, including white actors playing the caricatured roles of characters of colour in the early 1900s, paved the way for a persistent and nuanced media portrayal of the 50s – mid-60s as universally whitewashed and utopian.10,11,12

For many of us, a carousel of curated media images of these decades is ingrained in our memory. The boom-time economy generated a plethora of aspirational campaigns, most produced by Madmen-style agencies featuring picture-perfect homes, shiny aerodynamic cars, and modern conveniences for happy housewives. Pop culture of the time reflected more of the same with quaint families, such as the Cleavers, whose weekly escapades ignored the imbalance of capitalism, colonialism, and racial injustice.

The spectre of this utopian world gave comfort to a population that saw themselves reflected as safe, happy and racially homogenous. Contrarily, the portrayal of visible minorities at this time laid the foundation for the skewed narratives that continue to feed racist tropes to this day. Routinely characterized as threatening, oversexualized, lazy and uncivilized, there was no version of utopia where we, as BIPOC, held similar aspirations for ourselves and our families.10 As Dr. Herman Gray observed, Black television characters during the 1950s were “happy-go-lucky social incompetents,” serving only to amuse and comfort “white superiority and paternalism.” And while we could be entrusted to care for white children or clean white households, we could not be “trusted with the social and civic responsibilities of full citizenship as equals to whites.”13

The resurgence of nostalgia in media to romanticize and revive Cleaver-like times paired with the unchecked disparaging of visual minorities is deceptive and problematic. It panders to the fears of a white patriarchal hierarchy currently facing a very different reality. One in which the pristine middle class they aspire to is shrinking, the abundant manufacturing jobs which afforded them picture-perfect suburban homes are disappearing and advances in civil/human rights and immigration have opened global markets; thwarting their dreams of luxury, comfort and homogeneity.14

To say that ‘Times were better then,’ glosses over the grave hardships our communities faced and continue to face – the many times our lives are consistently and, at times, brutally whiplashed into states of fight or flight.

Reflecting on how these ideologies shape our collective worldview, I think of Chantal Gibson’s altered texts. In her work, Gibson underlines our exposure at a young age to images and narratives such as the Tar Baby story that encourage misrepresentation and, at times, violence against Black bodies. ‘What sticks?’ Gibson asks while slowly dripping liquid rubber in her films A Substance of Character (2016) and dangling modifiers (2022). How much of what we learn as children becomes inherently acceptable? How complicit are educators and parents in the continued retelling of these stories?

Gibson’s coverage of texts, braids and walls with this thick black substance plays with temporality, allowing us to think critically about the normalization of these narratives as a foundation for bias, hatred and discrimination through racial stereotyping. The archetypal imagery found in children’s readers and the systemic erasure of Blackness from historical texts lay the groundwork for cultural insensitivity while opening the door to race-based bullying in childhood and micro and macro aggressive racial slurring and abuse in adulthood. By literally and figuratively snuffing out these narratives and rendering texts unreadable, Gibson smothers dominant histories while making space for Black stories to be told.

The reach of these tropes extends far beyond the classroom. For BIPOC, childhood relationships, hopes, dreams and familial homes are often impacted by the spectre of colonialist ideals as we navigate questions of belonging. For Alyssa Bistonath, a childhood encounter with a playmate who characterized her skin as dirty ultimately led her to question the value attributed to the trophies of colonial cultures, such as her mother’s fine British china.

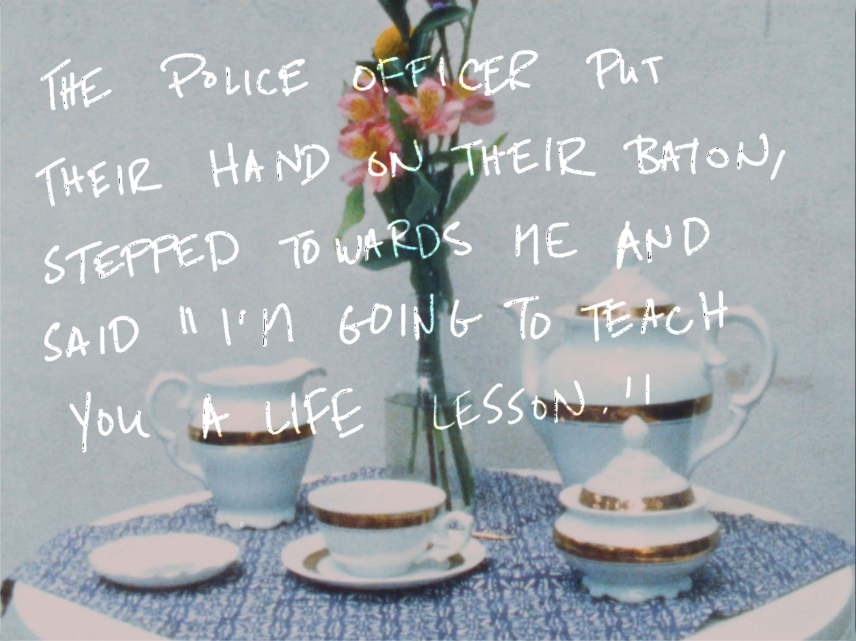

In the short film Dirt.Brown.Chocolate. (2022), Bistonath takes a knowing sip of tea from an ornate porcelain cup lined with gold trim. The moment appears alongside archival familial images and handwritten texts outlining her experiences with overt and subtle racism and colourism. With its nod to Bistonath’s Guyanese heritage and the 16th-century global sugar trade, bolstered by the European demand for tea and chocolate, Dirt.Brown.Chocolate. affirms the artist’s realization that the colour of her skin takes pride of place in a culture of whiteness.

The fineries in her childhood home that her parents, like many other immigrant families, believed might put them on equal footing with their white contemporaries did little to stunt the painful blows of discrimination in the outside world. Amassing the trophies of a dominant culture while simultaneously not being accepted by that culture is, in the end, an exercise in futility. Dirt.Brown.Chocolate. reflects markedly on the nostalgic notion of belonging, especially in the face of constant rejection and ridicule. More importantly, it questions why we need to fit in at all.

The resurgence of nostalgia in media to romanticize and revive Cleaver-like times paired with the unchecked disparaging of visual minorities is deceptive and problematic.

A consequence of nostalgic revival is the renewed call for assimilation in the form of rigid and, at times, nationalistic immigration policies encouraging us to “leave or remain”15, “build that wall”16 or pack the unwanted onto planes, trains and automobiles back to where “they” came from.17,18 It is a simplistic view that begs the question of whom shall we conform to? And to what end and whose comfort? When there is an inability to empathize with the many reasons why BIPOC choose to leave their home country or fight to stay in it, hoping to secure a piece of this utopian ideal for themselves, who do we become as a culture, society or human race? At what point does nostalgia devolve into desensitization?

Janice Chung’s work exemplifies why the immigration experience for visible minorities is layered and complex. Her intimate photography series of twenty-four images titled Please Come Back Soon (2014), includes scenes from her grandparents’ home and the province of Gyeonggi, Korea. These images, in step with the progression of her three visits, grapple with the heartbreaking separation many must face when leaving the only home and family they have ever known. An intense amount of resilience is required to adapt to a culture where the overriding demand is to relinquish all semblance of self to assimilate or face ostracization. Particularly, when there is no way to truly assimilate if you are visibly not in alignment with whiteness.

Chung’s work quietly lays bare the disruption of familial bonds through the tension of her mother’s return to Korea after a 10-year absence. The documentation and juxtaposition of these interactions between mother and family in Please Come Back Soon (2014) and mother and daughter through a series of haunting voicemails in the short film Bibi Ann (2014) illustrate that with distance, one must also accept irreversible loss and disconnection to heritage, history and culture. Does this intergenerational and transcontinental immigrant journey find a place of peace or reward? Perhaps our not knowing is what makes the work so enticing. It is consistent in its grief and, in some ways, represents a side of life that many BIPOC can relate to. In the end, the sacrifice required in the rebuilding of self to assimilate potentially means the loss of other parts of oneself forever.

Where Chung’s works focus on the familial cost of assimilation, Dima Srouji’s Sebastia (2020) centres on the land. Her short film opens with a sweeping musical composition accompanied by dreamy visuals of Palestine in nostalgic footage from her grandfather. Slowly we transition to the present day and the music darkens as we dive into the history of the area’s occupation. Srouji, an artist, educator and architect, uses her background in architecture to reveal forgotten and silenced narratives in the global south, particularly, Palestine. Through painstaking research, archival imagery and on-the-ground interviews, she documents the haphazard excavations of Sebastia, beginning in the early 1900s, and the ongoing tensions between the area’s Palestinian residents, rapidly encroaching settler developments and Israeli military.

Sebastia (2020) not only fills in some of the gaps of history concerning the removal of precious artifacts from the region, it sheds light on the present-day stories ignored by mass media. Srouji spotlights the region’s olive and apricot farmers and their plight to continue tending to the land while not shying away from revealing the ensuing skirmishes that result. Her work challenges the prevailing narrative and tables difficult questions of who should own or reclaim the land that those who lay claim to indigeneity have long called home.

In complement to Sebastia (2020), Srouji's fragile Ghosts (2022), glass replicas of displaced artifacts, embedded in a reconstructed dig site as part of Maternal Exhumations (2022), act not only as place markers of what was but also of what can never be replaced in the harsh literality of the Harvard Excavations. Even though Srouji employs different approaches to the same theme with Sebastia (2020) and accompanying ephemera – one very heavy, the other incredibly light – both have the potentiality to bring forth the same response from an encounter with her work, empathy.

At what point does nostalgia devolve into desensitization?

All too often, we have seen that for the dominant it is easy to have little to no interest in understanding the plight of those whose existence is akin to a blip in the grander scheme of hegemony except to ensure they do not encroach too closely upon it. This fear of growing smaller overtakes the ability to reason, listen and understand. To play on those fears through the use of nostalgic propaganda not only infers that the simpler times of old, when the aspirations of the other were held in check by borders, Jim Crow laws, Head Taxes and Residential Schools, were idyllic, it paves the way for stereotypical narratives attributed to our communities to be woven into political campaigns that bolster public support for discriminatory policies. We need only look to the decimation of Africville in Halifax, Nova Scotia19 under the guise of unsafe living conditions, the forced assimilation and abuse of Indigenous children in Residential Schools20,21 and the numerous policies restricting Asian, Black, Indigenous and South Asian voting rights in Canada to see the generational impact of these tactics.22

The consistent use of whitewashed nostalgia also encourages the characterization of BIPOC histories as too uncomfortable to face or relate to in any meaningful way. Examples can be seen in the current fight to suppress Critical Race Theory which contextualizes the relationship between racism and public policy and, The 1619 Project which reframes American history by placing the consequences and contributions of slavery at the core of its narrative.23 This is why the arduous work of reclaiming our histories is of critical importance to our communities and in this exhibition, the artists Joi T Arcand, Shellie Zhang and Caroline Monnet foreground this resistance.

Joi T. Arcand's preservation of language and tradition in she used to want to be a ballerina (2019) reinforces that the call of assimilation is one we can ignore. As a child, Arcand also felt the power of media portrayals of whiteness as the standard and had dreams of becoming a ballerina in the vein of Anna Pavlova. Realizing that those aspirations were not possible on a remote reserve, she immersed herself for a time in the traditions of Powwow dancing with the help of her grandmother. Her work deftly connects the oppressive colonial legacies that restricted the practice of Indigenous language and traditions with the reclamation of those legacies.

Arcand reimagines the classically designed music box by infusing it with the sound of Buffy Sainte Marie’s, ”She Used to Wanna Be a Ballerina” and covering it with stickers and letters spelling “kiya” and “i.tako” meaning “be you.” She challenges the expected visual of pink ballet slippers and tutu with backlit photos of her bare feet set in ballet positions while dressed in traditional regalia. And, she coopts the neon sign, the epitome of North American nostalgia, with text written in Plains Cree, ē-kī-nōtē-itakot opwātisimowiskwēw (she used to want to be a fancy dancer) (2019) all in homage to Maria Tallchief, the first Indigenous American ballerina. Arcand dares us to imagine what spaces would be like if roles were reversed. Through a melody of media, we are encouraged to immerse ourselves in the world as seen through her lens as colonial narratives are dimmed allowing alternative perspectives to shine through.

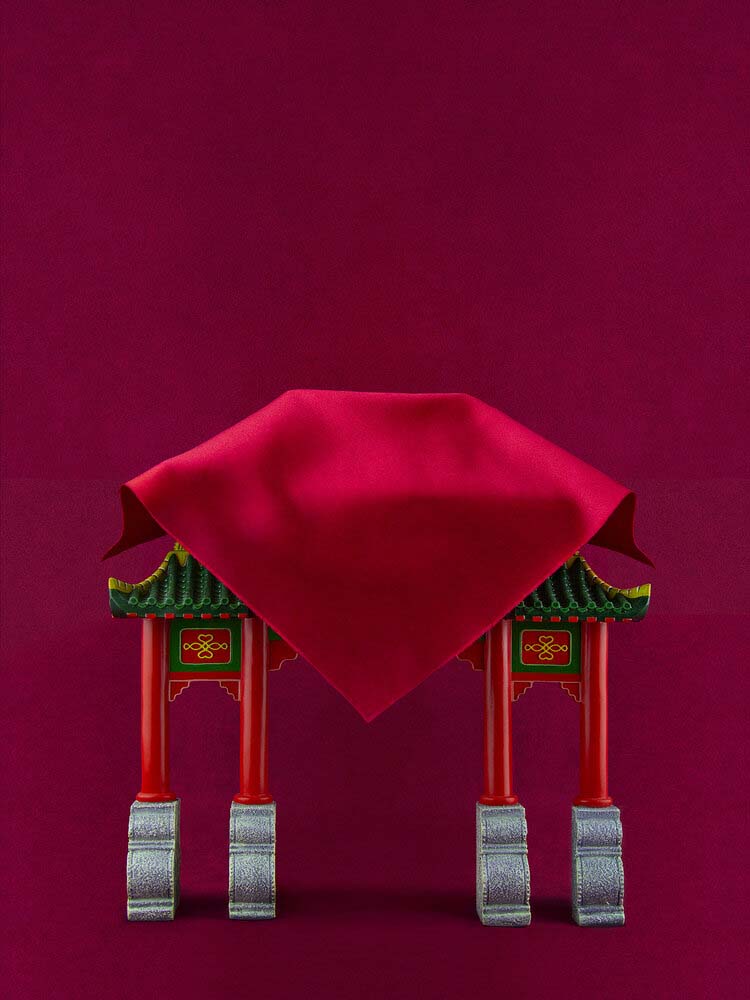

Continuing the conversation around rewritten histories is Shellie Zhang’s Believe It or Not (2020-2021), in which the artist traces the Chinese experience in mid-Western Canada. Demonstrating the limitations of truth in an age of fake news, Zhang tackles “...the politics of believability” for legacies outside of colonial narratives. Through a Clue-like and colourful series of six photographs paired with matching colour-coded archival materials, the artist reverses the persistent stereotype of Chinese Canadians as silent and woefully obedient while highlighting patterns of displacement and discrimination.

Zhang presents a community willing to stand up and fight back in the recounting of stories such as the Supreme court battle against discriminatory hiring legislation in Help Wanted: The Curious Case of Quong Wing v.R and the use of petitions to counter punishingly high taxes levied against Chinese laundries in Strength in Numbers: Wing Lee Laundry and the Saskatoon Chinese Laundry Petition. Zhang’s work posits, how much more can we achieve when we band together to counter these legislations? And, when faced with the possible loss of all we have built, what do we have to lose?

Believe It Or Not (2020-2021), is a testament to the determination of the Chinese community and their efforts to make space for themselves in unwelcoming cities. By holding up these histories, such as that of the Wong brothers and the Chinatown Gate, Zhang subsumes and pays tribute to them while countering a persistently redacted narrative.

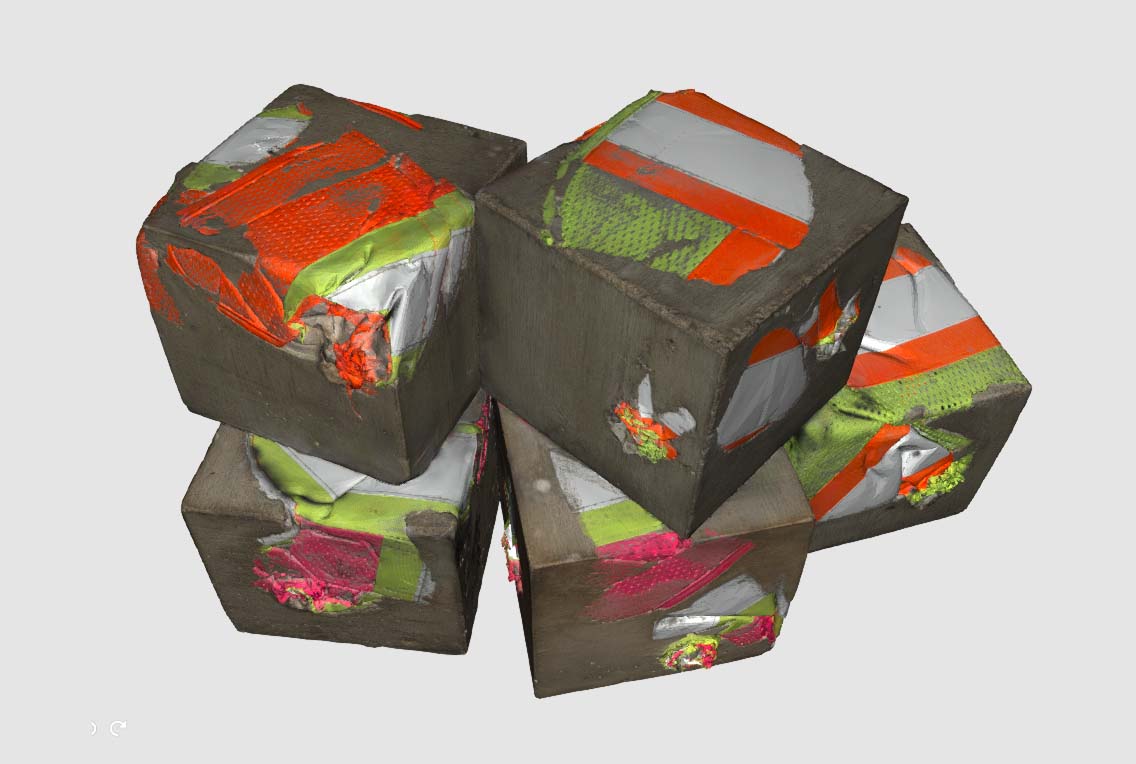

The use of legislation as a means of suppression is a central theme of Caroline Monnet’s Deer In Headlights (2022), in particular the aggressive political agendas employed to infantilize and repress the rights of Indigenous peoples. The piece consists of fifty-three cement blocks embedded with strips of fluorescent visibility workwear fabric, one block for each year the Indigenous were given the right to vote. Monnet notes that Quebec was the last province to grant this right to First Nations on May 2, 1969; a date that seems unbelievably recent. The assemblage of the blocks as puzzle pieces is reminiscent of architectural models and building materials used for purposes of scale, a new area of exploration for the artist. Monnet states:

“I’m continuing this exploration of building materials and trying to push it…more towards architecture and how architecture can…play a role in reconciliation. Architecture hasn’t been seen as something friendly in the past. For Indigenous people, it’s a symbol of colonization, it represents sedentary life and, residential school and housing in reserve. I’m hoping…to create new works that offer new models of dialogue...” (Arsenal, 2021)

As Canada, confronts its colonial past with the devasting and ongoing discovery of mass graves on residential school sites, we are not wrong to question the whitewashed narrative of this country’s history as that of the settler. In 2022, there are still First Nations communities living under boil water advisories and parts of the invasive and paternalistic Indian Act of 1892 restricting language, movement and even marriage for the Indigenous remain as they were when first drafted. In exploring the strength and, at times, precarious nature of building materials, Monnet’s willingness to rework and expand on themes of reconciliation through architectural forms is inspiring. Her sculptural works are a weighty and welcome intervention into spaces once limited to discourses of whiteness.

The consistent use of whitewashed nostalgia also encourages the characterization of BIPOC histories as too uncomfortable to face or relate to in any meaningful way.

While I am buoyed by the continued defiance of our communities, in the wake of a global pandemic and a continuing campaign of media disinformation driving exploding numbers of xenophobia, I wonder how much longer must we resist?24,25,26,27,28,29 If anything, the pandemic has reinforced our inequality. For the Asian community, it was the consistent barrage of anti-Asian sentiment spewed from the White House to the evening news culminating in 90 and 301% increases in random verbal and physical attacks in the US and Canada, respectively.30,31 For migrants, the Indigenous and visible minorities, COVID-19 ushered in second and third waves of increased food insecurity and skyrocketing mortality rates; the consequences of punitive legislative policies hastily invoked to lock borders coupled with inequitable access to healthcare and a lack of safe spaces to shelter in place.32

The enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions also fostered the expansion of policing measures, correlating with a marked increase in police brutality worldwide, targeting “marginalized groups such as racial and ethnic minorities, migrants, and the poorest members of society” with deadly consequences.33 In Toronto, where I live, a recent study revealed that Blacks are 230% more likely to be met with a gun when engaging with police.34 230%. Is this the “great” America we should revere? Are these skewed values the ones that BIPOC should “stand up for?”

While I am buoyed by the continued defiance of our communities, in the wake of a global pandemic and a continuing campaign of media disinformation driving exploding numbers of xenophobia, I wonder how much longer must we resist?

When I think about resistance in the age of nostalgia and the question of temporality, I think of the sheer force and determination of multidisciplinary artist Howardena Pindell and her fight against institutional violence. In 1980, after a car accident left Pindell with a traumatic brain injury, she focused the camera on herself as a means of catharsis and filmed Free, White and 21 (1980). The piece, a response to her frustrations with a women’s movement that failed to recognize the struggles of women of colour, is a first-hand account of the racism she experienced as a Black woman in America. In it, Pindell takes the viewer through a series of racially insensitive micro and macro aggressions levied at her mother and then herself while playing both herself and an aggressively dismissive white woman.

Pindell’s work highlights the role of hegemony in both art institutions and the feminist movement. In particular, the resistance to her work and the works of other BIPOC artists, while white women artists in the movement were able to secure gallery representation and exhibitions. As Pindell states;

“The white voice was to be the dominant voice; its goals were to be the dominant goals. The collectives in the 1970s were often predominantly white. If they were not in charge, then business was not to be conducted.

It was about domination and the erasure of experience, cancelling and rewriting history in a way that made one group feel safe and not threatened. I call it the “Hatshepsut maneuver.” The pharaohs who followed Hatshepsut’s reign removed the cartouche in an attempt to cancel out her place in history. In this case, the white women were removing the cartouches of women of color.”35

Pindell’s continued work as a treasured curator, artist, educator and activist emphasizes that as we address issues of dominance in the societal landscape, we must also address its ties to systemic issues within the cultural institutions we engage with. Decades after Pindell’s experiences with white feminists in the art world and her accounts of their lack of empathy toward the struggle of BIPOC women, we still find ourselves having the same conversation about erasure and place. Though her white alter ego in Free, White and 21(1980) believes Pindell “…won’t exist until we validate you”, a shift in that thinking is upon us.

The recent outpouring of personal experiences and calling to account on social media, amid the Black Lives Matter movement, aided the exposure of the performative nature of institutions.36,37,38 From the handling of BIPOC contributions to the questionable respect shown to the BIPOC artists, gallerists and curators “invited” to share their knowledge, institutions would do well to be more of a reflection of the world around them and not the boards and donors sitting far removed above them.

In the end, if the whitewashed image of a Cleaver-like utopia is the benchmark to which we should all aspire, what happens when those aspirations were never meant for you? If nostalgia is defined as “a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past,” can we, as BIPOC, truly share the same sentiment with our complex histories marred by colonialism, forced assimilation, dehumanization, and erasure of traditions? Given all of the above, the premise is unlikely.

In the end, if the whitewashed image of a Cleaver-like utopia is the benchmark to which we should all aspire, what happens when those aspirations were never meant for you?

Yet, though I too am weary, I feel a glimmer of hope. And that hope lies in us. Although even the journey to this presentation was in itself long and fraught, I continue to be honoured and exhilarated by the generosity, insight and talent of the artists in this exhibition. Their determination to disseminate these challenging histories allowed me to forge ahead in this realization. Being in communion with them has cemented to me that taking space for us to share the memories, heritage, and experiences that shape our reality is vital. Not for explanation or debate, for we need not justify our presence, but for reclamation and resistance.

Nostalgia, for us, has not been a rose-coloured journey, but instead a rollercoaster of sparse highs and crushing lows. If the world will not stop this consistent whiplash, and we cannot expect it will, then it falls to us to do so for ourselves. And so, we shall, while taking rest, seeking communion in allied spaces and, most importantly, getting very comfortable with saying no.

References

1. Ramírez, Nikki McCann. “A Racist Conspiracy Theory Called The ‘Great Replacement’ Has Made Its Way from Far-Right Media to the GOP.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 7 Sept. 2020, www.businessinsider.com/racist-great-replacement-conspiracy-far-alt-right-gop-mainstream-2020-9.

2. Carpenter, Lorraine. “The Trucker Convoy Organizer Is an Islamophobic, Homophobic Conspiracy Theorist.” Cult MTL, Cult MTL Media Inc., 28 Jan. 2022, cultmtl.com/2022/01/the-canadian-trucker-convoy-organizer-is-an-islamophobic-homophobic-conspiracy-theorist/).

3. Bernstein, Joseph. “Here’s How Breitbart and Milo Smuggled Nazi and White Nationalist Ideas into the Mainstream.” BuzzFeed News, BuzzFeed News, 26 Oct. 2019, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/josephbernstein/heres-how-breitbart-and-milo-smuggled-white-nationalism.

4. Ling, Justin. “We Went to Kellie Leitch’s Campaign Launch to Hear Her Immigrant Screening Pitch.” Vice, Vice Media Group, 17 Oct. 2016, www.vice.com/en/article/vdqnaa/we-went-to-kellie-leitchs-campaign-launch-to-hear-her-immigrant-screening-pitch.

5. Lopez, German. “The Most Striking Photos from the White Supremacist Charlottesville Protests.” Vox, Vox Media LLC, 12 Aug. 2017, www.vox.com/identities/2017/8/12/16138244/charlottesville-protests-photos.

6. White, Jeremy B., et al. “What Charlottesville Changed.” POLITICO Magazine, www.politico.com, 12 Aug. 2018, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/08/12/charlottesville-anniversary-supremacists-protests-dc-virginia-219353/.

7. Skutsch, Carl. “The History of White Supremacy in America.” Rolling Stone, Penske Media Corporation, 25 June 2018, www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/the-history-of-white-supremacy-in-america-205171/).

8. Gray, Rosie. “Trump Defends White-Nationalist Protesters: ‘Some Very Fine People on Both Sides’.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 9 June 2021, www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/08/trump-defends-white-nationalist-protesters-some-very-fine-people-on-both-sides/537012/.

9. Smith, Dr. Stacey L., et al. Annenberg Foundation, 2016, pp. 2–23, Inequality in 800 Popular Films: Examining Portrayals of Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBT, and Disability from 2007-2015.

10. ‘‘Bamboozling’ Stereotypes Through the 20th Century.” Racism, Sexism, and the Media: Multicultural Issues into the New Communications Age, by Clint C. Wilson et al., SAGE Publications, 2013, pp. 68–98.

11. “Theoretical Foundations of Research in Mass Media Representations.” Diversity in US Mass Media, by Catherine A. Luther et al., Second ed., Wiley Blackwell, 2018, pp. 19–21.

12. “Representations of African Americans.” Diversity in US Mass Media, by Catherine A. Luther et al., Second ed., Wiley Blackwell, 2018, pp. 51–54.

13. Gray, Herman. “Politics of Representation in Network Television.” Watching Race: Television and the Struggle for Blackness, by Herman Gray, University of Minnesota Press, 2005, pp. 75.

14. Rapp, Nicolas, and Matthew Heimer. “The Shrinking Middle Class: By the Numbers.” Fortune, Fortune Media IP Limited, 20 Dec. 2018, fortune.com/longform/shrinking-middle-class-math/.

15. Surridge, Paula, and Dr Alan Wager. “Leave vs. Remain: Is Brexit Still the Main Divide in British Politics?” UK in a Changing Europe, ESRC, 15 Dec. 2021, ukandeu.ac.uk/leave-vs-remain-brexit-british-politics/.

16. Rodriguez, Sabrina. “Trump’s Partially Built ‘Big, Beautiful Wall’.” POLITICO, Politico LLC, 1 Dec. 2021, 13:53, www.politico.com/news/2021/01/12/trump-border-wall-partially-built-458255.

17. BBC. “Windrush Generation: Who Are They and Why Are They Facing Problems?” BBC News, BBC Global News Ltd, 24 Nov. 2021, www.bbc.com/news/uk-43782241.

18. Krauss, Joseph. “Palestinians Fear Loss of Family Homes as Evictions Loom.” AP NEWS, Cowles Publishing Co. The Ogden Newspapers Inc., 10 May 2021, apnews.com/article/middle-east-religion-2ba6f064df3964ceafb6e2ff02303d41.

19. Loo, Tina. “View of Africville and the Dynamics of State Power in Postwar Canada: Acadiensis.” View of Africville and the Dynamics of State Power in Postwar Canada | Acadiensis, Acadiensis, 6 June 2010, journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/view/18419/19899.

20. Décoste, Rachel. “The Most Discriminatory Laws in Canadian History.” HuffPost, BuzzFeed, Inc., 16 Nov. 2013, www.huffingtonpost.ca/rachel-decoste/most-discriminatory-canadian-laws_b_3932297.html.

21. Palmer, Howard, and Leo Driedger. “Prejudice and Discrimination in Canada.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, 10 Feb. 2011, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/prejudice-and-discrimination.

22. Courtney, John C. “Right to Vote in Canada.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 18 Mar. 2007, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/franchise.

23. Wong, Julia Carrie. “The Fight to Whitewash US History: ‘a Drop of Poison Is All You Need’.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 25 May 2021, www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/25/critical-race-theory-us-history-1619-project.

24. CBC News. “5 Years after Fatal Mosque Attack, Quebec City Muslims Call for CAQ Government to Do More to End Islamophobia | CBC News.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 27 Jan. 2022, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-city-muslim-community-more-action-needed-1.6329785.)

25. Montpetit, Jonathan. “Quebec City Mosque Shooting.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 29 Apr. 2019, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/quebec-city-mosque-shooting.

26. Stevenson, Verity. “'We Will Keep on Fighting': Muslim Women Devastated by Appeal Court Decision to Uphold Bill 21 | CBC News.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 13 Dec. 2019, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/court-of-appeal-bill-21-reaction-1.5392522.)

27. Ura, Alexa. “A Racist Manifesto and a Shooter Terrorize Hispanics in El Paso and Beyond.” The Texas Tribune, The Texas Tribune, 5 Aug. 2019, www.texastribune.org/2019/08/05/hispanics-terrorized-after-el-paso-shooting-and-racist-manifesto/.

28. Beckett, Lois. “More than 175 Killed Worldwide in Last Eight Years in White Nationalist-Linked Attacks.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media,5 Aug. 2019, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/aug/04/mass-shootings-white-nationalism-linked-attacks-worldwide.

29. Ruiz, Rebecca. “When You Become the Target of Racist Disinformation.” Mashable, Ziff Davis, 29 Oct. 2021, mashable.com/article/covid-19-disinformation-anti-asian-racism.)

30. Press, The Associated. “More than 9,000 Anti-Asian Incidents Have Been Reported since the Pandemic Began.” NPR, NPR, 12 Aug. 2021, www.npr.org/2021/08/12/1027236499/anti-asian-hate-crimes-assaults-pandemic-incidents-aapi.

31. Yun, Tom. “Police-Reported Anti-Asian Hate Crimes in Canada Jumped 300 per Cent in 2020: Statcan.” CTVNews, Bell Media, 18 Mar. 2022, www.ctvnews.ca/canada/police-reported-anti-asian-hate-crimes-in-canada-jumped-300-per-cent-in-2020-statcan-1.5823965.)

32. Gruer, Laurence, et al. “Migration, Ethnicity, Racism and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Conference Marking the Launch of a New Global Society.” Public Health in Practice, Elsevier, 10 Feb. 2021, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666535221000136.

33. OMTC. “Thematic Briefing Report : The Extra-Custodial Use of Force Amounting to Torture and Other Ill-Treatment.” OMTC, 17 Mar. 2021.

34. Harmsen, Natalie. “Toronto Police Data Reveals Black People Face Most Use of Force.” Complex, Complex Media, Inc. , 15 June 2022, www.complex.com/life/toronto-police-report-2022-use-of-force.

35. Pindell, Howardena. “On Making a Video: Free, White and 21.” THE HOWARDENA PINDELL PAPERS, MCA Chicago, 1 Feb. 2019, pindell.mcachicago.org/the-howardena-pindell-papers/on-making-a-video-free-white-and-21-1992/.

36. Morris, Carmen. “Performative Allyship: What Are the Signs and Why Leaders Get Exposed.” Forbes, Forbes, Inc., 10 Dec. 2021, www.forbes.com/sites/carmenmorris/2020/11/26/performative-allyship-what-are-the-signs-and-why-leaders-get-exposed/?sh=25a7c52e22ec.

37. Carrigan, Margaret. “How the Art Industry Is Grappling with Its Systemic Race Inequality.” The Art Newspaper - International Art News and Events, The Art Newspaper SA, 28 Sept. 2021, www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/07/10/how-the-art-industry-is-grappling-with-its-systemic-race-inequality.

38. Ware, Syrus Marcus, et al. “Give Us Permanence-Ending Anti-Black Racism in Canada's Art Institutions.” Canadian Art, Canadian Art, 25 Jan. 2021, canadianart.ca/features/give-us-permanence-ending-anti-black-racism-in-canadas-art-institutions/.