Artist

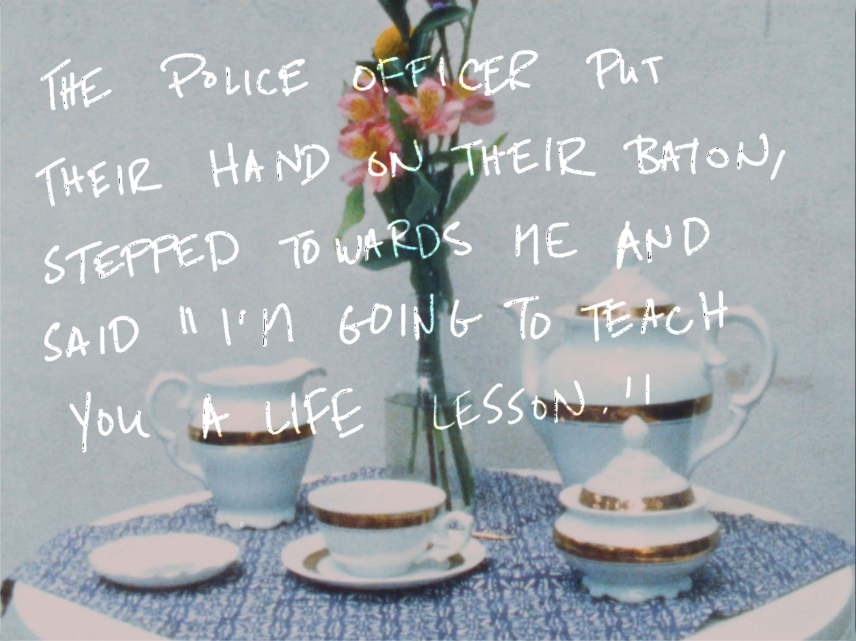

Free, White and 21, 1980 / Video Stills

HOWARDENA

PINDELL

In 1979, after a devastating car accident left her with partial memory loss, Howardena Pindell filmed Free, White and 21. In some ways, the piece functioned as a means of catharsis during a difficult recovery. Speaking directly to the camera both as herself and a 21-year-old white alter-ego, Pindell gives an unflinching account of the casual racism directed toward herself and her mother. Pindell notes her frustration with the lack of empathy and erasure of women of colour within a predominantly white feminist movement and the embedded systemic discrimination within art institutions that negatively impacted the opportunity and recognition of BIPOC artists. Free, White and 21 not only addresses the ability of systemic racism to determine the course of a life but also its prevalence within institutional systems.

Free,

White and 21

1980

Video (color, sound)

Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

I decided to make Free, White and 21 after yet another run-in with racism in the art world and the white feminists. I was feeling very isolated as a token artist. I found that white women wanted me to be limited to their agenda. When they were beginning to be represented by galleries and shown in exhibitions, women of color were rarely considered. Their omission was rarely noticed, except by a few. I was told I was jealous because I noticed and talked about it. Racism, as a constant assault in the daily lives of all people of color, was not a high priority for them. It was seen as “a cause,” “a special interest group,” “political”—something for their temporary concern if their attention was engaged. Some of the women of color who spoke out were considered “belligerent.” I remember hearing that the feminists wished I had been “cooperative.”

The white voice was the dominant voice. What the white male’s voice was to the white female’s voice, the white female’s voice was to the woman of color’s voice. The dominant voice was usually limited to the middle- and upper-class white women, but all classes of white women participated consciously or unconsciously in racism. (Several years after I made the tape, when I saw the ending, I felt that it was symbolic of the women’s auxiliary of the KKK. Instead of a white sheet, like a bank robber, the white character covers her face with a “polite” white stocking.) I remember hearing racism explained as a distraction from the real issues offered by the system, which needed a scapegoat. The white voice was to be the dominant voice; its goals were to be the dominant goals. The collectives in the 1970s were often predominantly white. If they were not in charge, then business was not to be conducted.

The white voice was to be the dominant voice; its goals were to be the dominant goals.

It was about domination and the erasure of experience, canceling and rewriting history in a way that made one group feel safe and not threatened. I call it the “Hatshepsut maneuver.” The pharaohs who followed Hatshepsut’s reign removed the cartouche in an attempt to cancel out her place in history. In this case, the white women were removing the cartouches of women of color.

I quit my job at the Museum of Modern Art in 1979 and started teaching. Although I was beginning to be outspoken about issues of de facto censorship and racism in the art world, my work as an artist was usually devoid of personal, narrative, or autobiographical reference. I considered myself fairly voiceless in those days. Several months after I started teaching, I was in a freak accident as a passenger in the back seat of a car on the way to my job. One minute I was fine, the next I was in an ambulance. I had amnesia—a temporary loss of some of my long- and short-term memory. I was also aware that there were those who were pleased: because of my injuries, there was the possibility of my voice being muted. I know now that the desire to keep me silent, and to be pleased that I might be, by default, forced into silence, was an extension of the legacy of slavery and racism. I remember the day, almost within the first hour that I returned from two weeks in the hospital, when I received a call from one of the white feminists who asked me for a recommendation. I tried to explain that I had been injured. She was insistent that I should write it for her as soon as possible. I never did write it, but was enraged by her need for me to provide a “service” with full knowledge that I was injured and would need time to recover. I have found the need for service to be a common trait of “liberal” racists, even those who call themselves progressive—the expectation that they must be served constantly no matter how inconvenient it is to others. Whites often find this funny, but they do not know what it is like to always be expected to be grateful, to be taken advantage of, and to be considered needless and wantless. The women’s movement often talks about this relative to men’s expectations of them, but they rarely talk about their expectations of women of color and all people of color, who frankly represent 85 percent of the planet.

1980

Video (color, sound)

Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

My work in the studio after the accident helped me to reconstruct missing fragments from the past. My parents lived with me for several months, as I was not strong enough to be on my own. I was very grateful for this. Eight months after the accident, I made Free, White and 21 in my top floor loft during one of the hottest summers in New York. The tape was autobiographical and pertained to a wide range of experiences, focusing on gender issues and race bias. I had faced de facto censorship issues throughout my life as part of the system of apartheid in the United States. In the tape, I was bristling at the women’s movement as well as at the art world and some of the usual offensive encounters that were heaped on top of the racism of my profession. The tape was first shown in an exhibition directed by Ana Mendieta at A.LR. Gallery when it was located on Wooster Street in Manhattan. The exhibition was called Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States (September 2–20, 1980). The artists included Judith Baca, Beverly Buchanan, Janet Olivia Henry, Zarina Hashmi, Senga Nengudi, Lydia Okumura, Selena Whitefeather, and myself. I understand that when my tape was entered in a video competition in 1980, the jury felt that it was too divisive.

I was feeling very isolated as a token artist. I found that white women wanted me to be limited to their agenda.

In the late 1980s, it became a kind of underground cult tape and was shown mainly in universities. Later, when it was to be included in one of my one-person exhibitions, a person who had written an essay for the catalogue asked me to remove it from the show. I, of course, refused. When the complaint was taken to the exhibition’s curator, he too refused to remove it. I have encountered various other reactions, including outrage from a white female critic as if I had some nerve talking about my experiences and upsetting her. I also heard that some of the white female students who saw it felt the same.

When I showed it to a New England university audience, a white woman student asked sarcastically if it made me feel better to have made the tape. When it was first shown in Dialectics of Isolation, a white male, an alumnus of one of the schools I attended and mentioned in the tape, said that he did not believe my experiences. Other artists of color have said that they felt it was not forceful enough or felt my experiences were in environments of privilege. When it was shown in a New Jersey museum, some of the older black security guards refused to turn on the video because they felt it was offensive to people of color. The tape officially begins my Autobiography series, which includes Scapegoat.

1980

Video (color, sound)

Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

My mother passed away in the summer of 1991, and in the painful sifting through of her things I have found pictures of her from the 1920s and discovered information about my family history, which has expanded my knowledge about who she was and how it affected my own experience. I found that she had attended white schools as the only black student, because her birth certificate said she was white, as did the birth certificates of her brothers and sisters. I cannot imagine the pain that she went through, the harassments and the taunts. She was deeply affected and scarred by it. I remember her stories about being the only black student in her class at Ohio State University and it being illegal for her to live in the dorm. It was illegal for people of color to use public facilities as well as public libraries. People would become impatient and aggressive if you even brought this issue up. It was always for their comfort to keep others down. Her harsh experiences reflected the tragedy that many families suffered in the aftermath of slavery. Many families were of very mixed race as a result of the massive sexual assault (as well torture and lynching) of the men, women, and children by the Europeans and their ancestors who had kidnapped Africans and held them hostage as slaves. I found on my father’s side that one of my relatives had been blinded by the lash of one of the enslaver’s whips. The history behind the rainbow of faces in my family on both sides led to many confusions. My mother’s face—a deep, rich brown—is my face. Coffee with cream, which was my aunt’s face, looked white. We would enter stores in Ohio in the 1950s and everyone would stare at us and I would panic. For years, I could not bear to look into a mirror. There were no positive images of my people in the media or magazines unless we favored European features; we were portrayed stereotypically to make others laugh, to make them comfortable and safe. Parts of the family passed and disappeared in Oklahoma.

Fear, I feel, motivates their silence, as the climate has become increasingly hostile, like the days when I grew up in a segregated city.

I recently found that my grandfather’s people were from Honduras. (I discovered this only after my mother passed away.) I have so many ancestral roots that l do not know where to start. Some of the family is very, very conservative, and I am the outspoken one. Fear, I feel, motivates their silence, as the climate has become increasingly hostile, like the days when I grew up in a segregated city.

Free, White and 21, 1980 / Video Stills

HOWARDENA PINDELL

Free, White and 21, 1980 / Video Stills

I decided to make Free, White and 21 after yet another run-in with racism in the art world and the white feminists. I was feeling very isolated as a token artist. I found that white women wanted me to be limited to their agenda. When they were beginning to be represented by galleries and shown in exhibitions, women of color were rarely considered. Their omission was rarely noticed, except by a few. I was told I was jealous because I noticed and talked about it. Racism, as a constant assault in the daily lives of all people of color, was not a high priority for them. It was seen as “a cause,” “a special interest group,” “political”—something for their temporary concern if their attention was engaged. Some of the women of color who spoke out were considered “belligerent.” I remember hearing that the feminists wished I had been “cooperative.”

The white voice was the dominant voice. What the white male’s voice was to the white female’s voice, the white female’s voice was to the woman of color’s voice. The dominant voice was usually limited to the middle- and upper-class white women, but all classes of white women participated consciously or unconsciously in racism. (Several years after I made the tape, when I saw the ending, I felt that it was symbolic of the women’s auxiliary of the KKK. Instead of a white sheet, like a bank robber, the white character covers her face with a “polite” white stocking.) I remember hearing racism explained as a distraction from the real issues offered by the system, which needed a scapegoat. The white voice was to be the dominant voice; its goals were to be the dominant goals. The collectives in the 1970s were often predominantly white. If they were not in charge, then business was not to be conducted.

It was about domination and the erasure of experience, canceling and rewriting history in a way that made one group feel safe and not threatened. I call it the “Hatshepsut maneuver.” The pharaohs who followed Hatshepsut’s reign removed the cartouche in an attempt to cancel out her place in history. In this case, the white women were removing the cartouches of women of color.

I quit my job at the Museum of Modern Art in 1979 and started teaching. Although I was beginning to be outspoken about issues of de facto censorship and racism in the art world, my work as an artist was usually devoid of personal, narrative, or autobiographical reference. I considered myself fairly voiceless in those days. Several months after I started teaching, I was in a freak accident as a passenger in the back seat of a car on the way to my job. One minute I was fine, the next I was in an ambulance. I had amnesia—a temporary loss of some of my long- and short-term memory. I was also aware that there were those who were pleased: because of my injuries, there was the possibility of my voice being muted. I know now that the desire to keep me silent, and to be pleased that I might be, by default, forced into silence, was an extension of the legacy of slavery and racism. I remember the day, almost within the first hour that I returned from two weeks in the hospital, when I received a call from one of the white feminists who asked me for a recommendation.

I tried to explain that I had been injured. She was insistent that I should write it for her as soon as possible. I never did write it, but was enraged by her need for me to provide a “service” with full knowledge that I was injured and would need time to recover. I have found the need for service to be a common trait of “liberal” racists, even those who call themselves progressive—the expectation that they must be served constantly no matter how inconvenient it is to others. Whites often find this funny, but they do not know what it is like to always be expected to be grateful, to be taken advantage of, and to be considered needless and wantless. The women’s movement often talks about this relative to men’s expectations of them, but they rarely talk about their expectations of women of color and all people of color, who frankly represent 85 percent of the planet.

My work in the studio after the accident helped me to reconstruct missing fragments from the past. My parents lived with me for several months, as I was not strong enough to be on my own. I was very grateful for this. Eight months after the accident, I made Free, White and 21 in my top floor loft during one of the hottest summers in New York. The tape was autobiographical and pertained to a wide range of experiences, focusing on gender issues and race bias. I had faced de facto censorship issues throughout my life as part of the system of apartheid in the United States. In the tape, I was bristling at the women’s movement as well as at the art world and some of the usual offensive encounters that were heaped on top of the racism of my profession.

The tape was first shown in an exhibition directed by Ana Mendieta at A.LR. Gallery when it was located on Wooster Street in Manhattan. The exhibition was called Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States (September 2–20, 1980). The artists included Judith Baca, Beverly Buchanan, Janet Olivia Henry, Zarina Hashmi, Senga Nengudi, Lydia Okumura, Selena Whitefeather, and myself. I understand that when my tape was entered in a video competition in 1980, the jury felt that it was too divisive.

In the late 1980s, it became a kind of underground cult tape and was shown mainly in universities. Later, when it was to be included in one of my one-person exhibitions, a person who had written an essay for the catalogue asked me to remove it from the show. I, of course, refused. When the complaint was taken to the exhibition’s curator, he too refused to remove it. I have encountered various other reactions, including outrage from a white female critic as if I had some nerve talking about my experiences and upsetting her. I also heard that some of the white female students who saw it felt the same.

When I showed it to a New England university audience, a white woman student asked sarcastically if it made me feel better to have made the tape. When it was first shown in Dialectics of Isolation, a white male, an alumnus of one of the schools I attended and mentioned in the tape, said that he did not believe my experiences. Other artists of color have said that they felt it was not forceful enough or felt my experiences were in environments of privilege. When it was shown in a New Jersey museum, some of the older black security guards refused to turn on the video because they felt it was offensive to people of color. The tape officially begins my Autobiography series, which includes Scapegoat.

My mother passed away in the summer of 1991, and in the painful sifting through of her things I have found pictures of her from the 1920s and discovered information about my family history, which has expanded my knowledge about who she was and how it affected my own experience. I found that she had attended white schools as the only black student, because her birth certificate said she was white, as did the birth certificates of her brothers and sisters. I cannot imagine the pain that she went through, the harassments and the taunts. She was deeply affected and scarred by it. I remember her stories about being the only black student in her class at Ohio State University and it being illegal for her to live in the dorm. It was illegal for people of color to use public facilities as well as public libraries. People would become impatient and aggressive if you even brought this issue up. It was always for their comfort to keep others down. Her harsh experiences reflected the tragedy that many families suffered in the aftermath of slavery. Many families were of very mixed race as a result of the massive sexual assault (as well torture and lynching) of the men, women, and children by the Europeans and their ancestors who had kidnapped Africans and held them hostage as slaves. I found on my father’s side that one of my relatives had been blinded by the lash of one of the enslaver’s whips. The history behind the rainbow of faces in my family on both sides led to many confusions.

My mother’s face—a deep, rich brown—is my face. Coffee with cream, which was my aunt’s face, looked white. We would enter stores in Ohio in the 1950s and everyone would stare at us and I would panic. For years, I could not bear to look into a mirror. There were no positive images of my people in the media or magazines unless we favored European features; we were portrayed stereotypically to make others laugh, to make them comfortable and safe. Parts of the family passed and disappeared in Oklahoma. I recently found that my grandfather’s people were from Honduras. (I discovered this only after my mother passed away.) I have so many ancestral roots that l do not know where to start. Some of the family is very, very conservative, and I am the outspoken one. Fear, I feel, motivates their silence, as the climate has become increasingly hostile, like the days when I grew up in a segregated city.

1980

Video (color, sound)

Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York